Last week I returned from a two-week observing trip on the side of Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawai'i.

The trip was kindly organised by Dave Kriege of Obsession Telescopes who visits the island annually and keeps an Argo Navis equipped 22" Obsession UC stored there at a house of a Keck Observatory worker.

Our primary observing spot was at 9,200' (2,804 m) point on Mauna Kea. At that altitude, you are typically above the cloud tops but just below the point where altitude sickness becomes a potential issue for most individuals.

Night time temperatures typically hovered just above the freezing point but the freezer suit and woollen gloves I packed for the trip made observing comfortable.

I must admit if felt weird pack cold weather gear for a trip to Hawaii.

Suffice to say the skies at that altitude on an island in the mid-Pacific whose relatively low population and enviable outdoor lighting ordinances are to die for. They are dark and transparent and the airglow

which is typically visible at the best dark sky locations at lower altitudes elsewhere on Earth is minimal.

The quality of the skies was first evidenced by the immediately apparent zodiacal light that extended up from the western horizon to perhaps 60 degrees elevation or more.

Caused by sunlight reflecting of particles of dust and ice in the solar system, as one of my observing colleagues said, if you didn't know better you would think there is a floodlit football stadium down there.

A couple of Sky Quality Meters gave SQM readings around the 22.18 on each night.

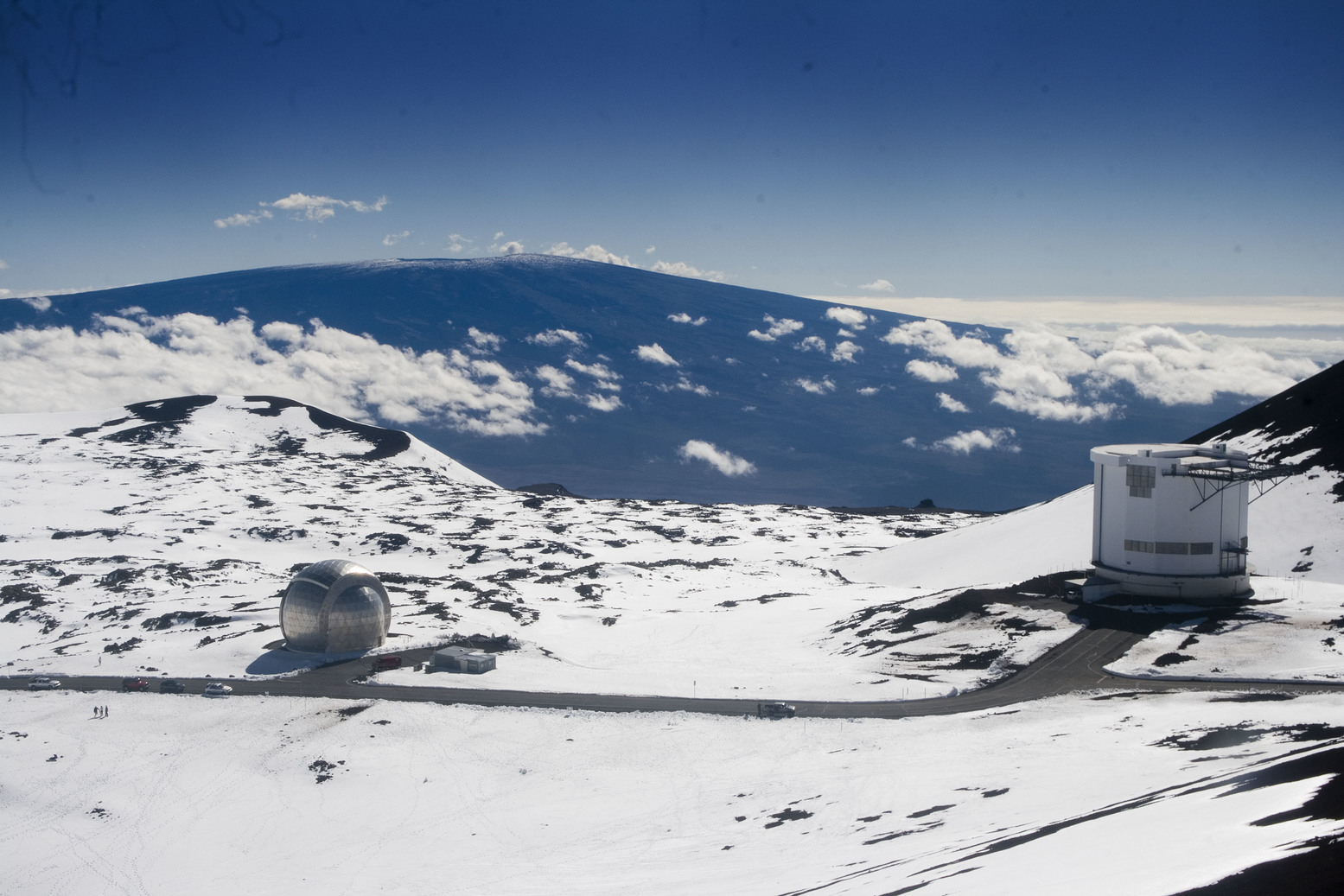

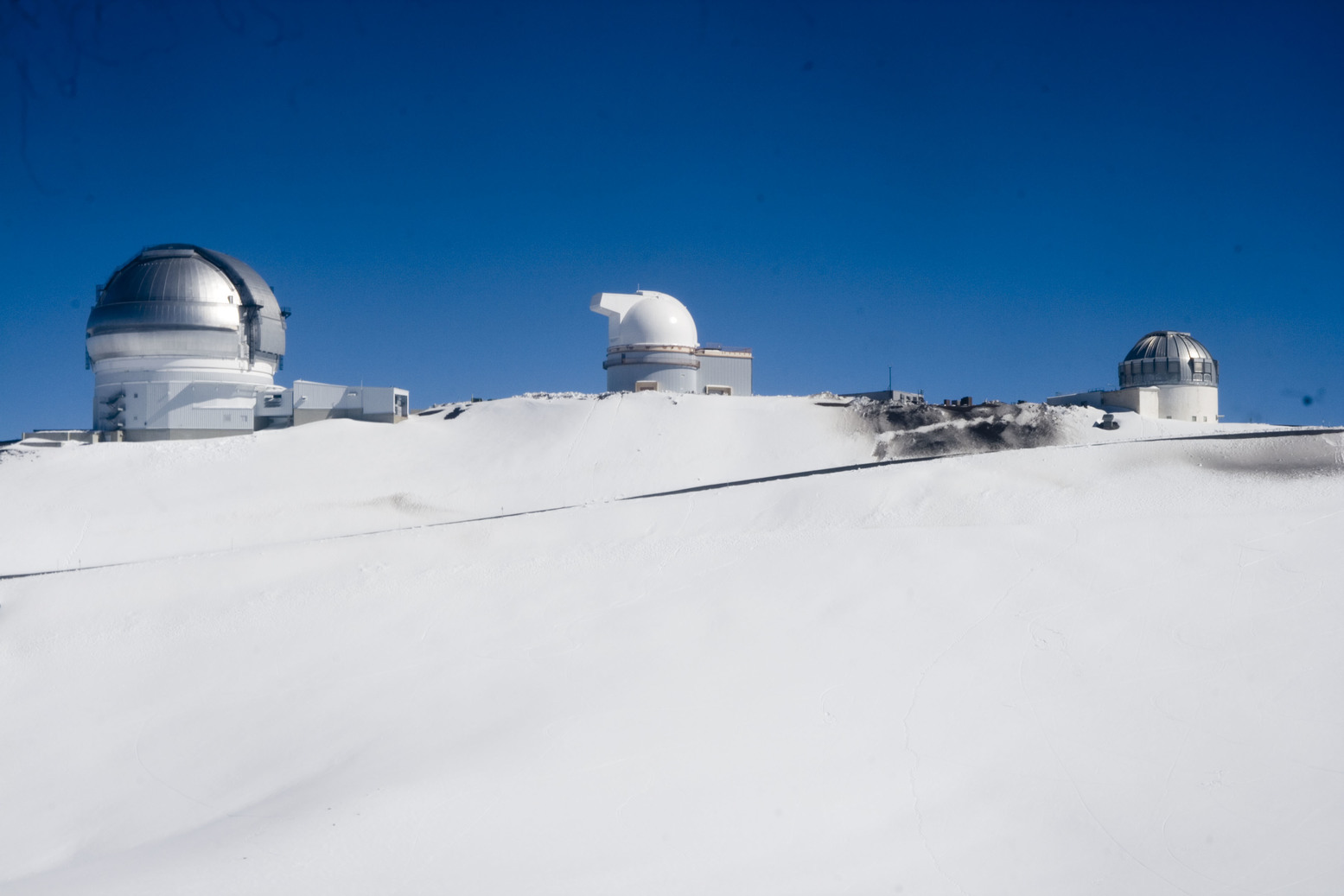

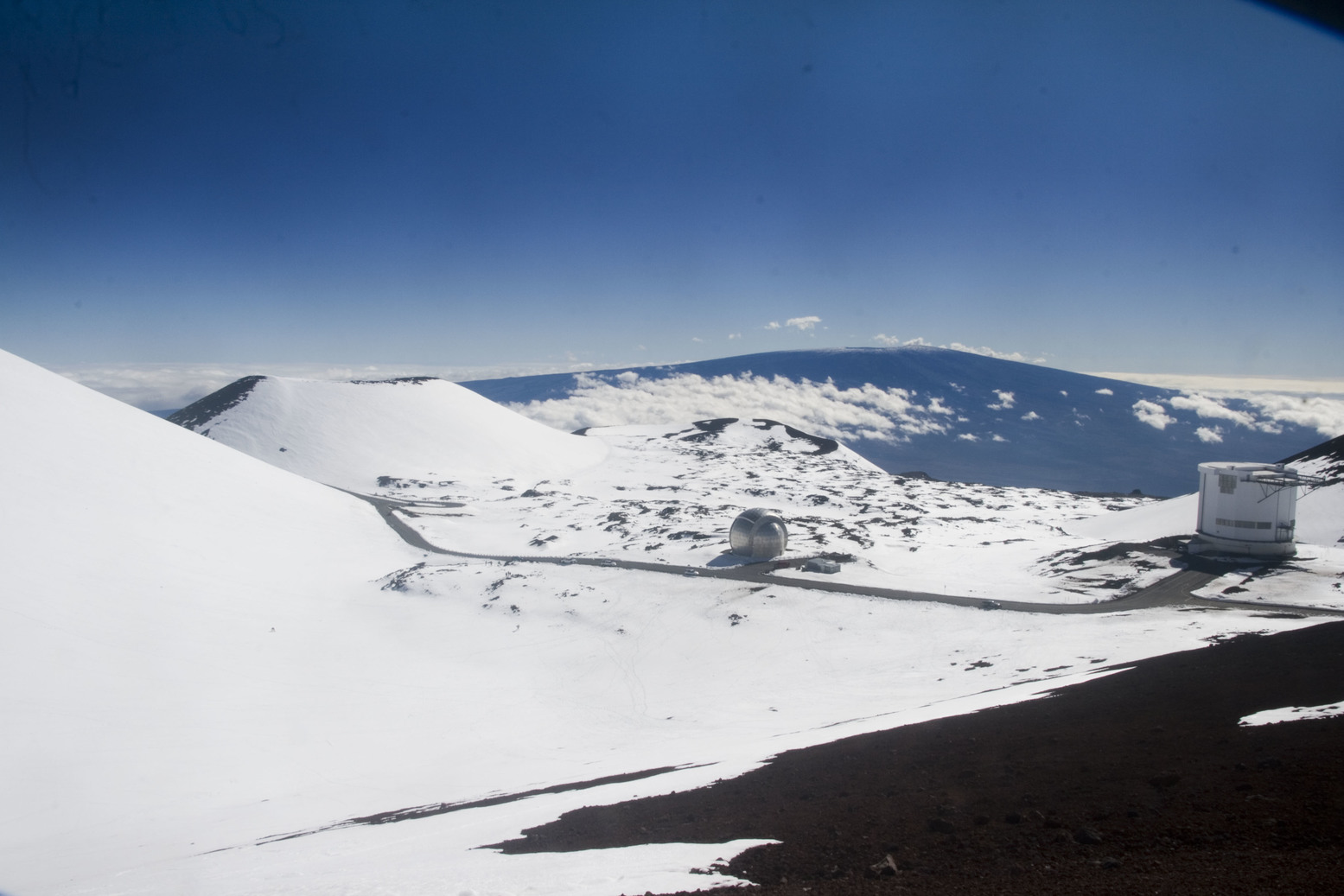

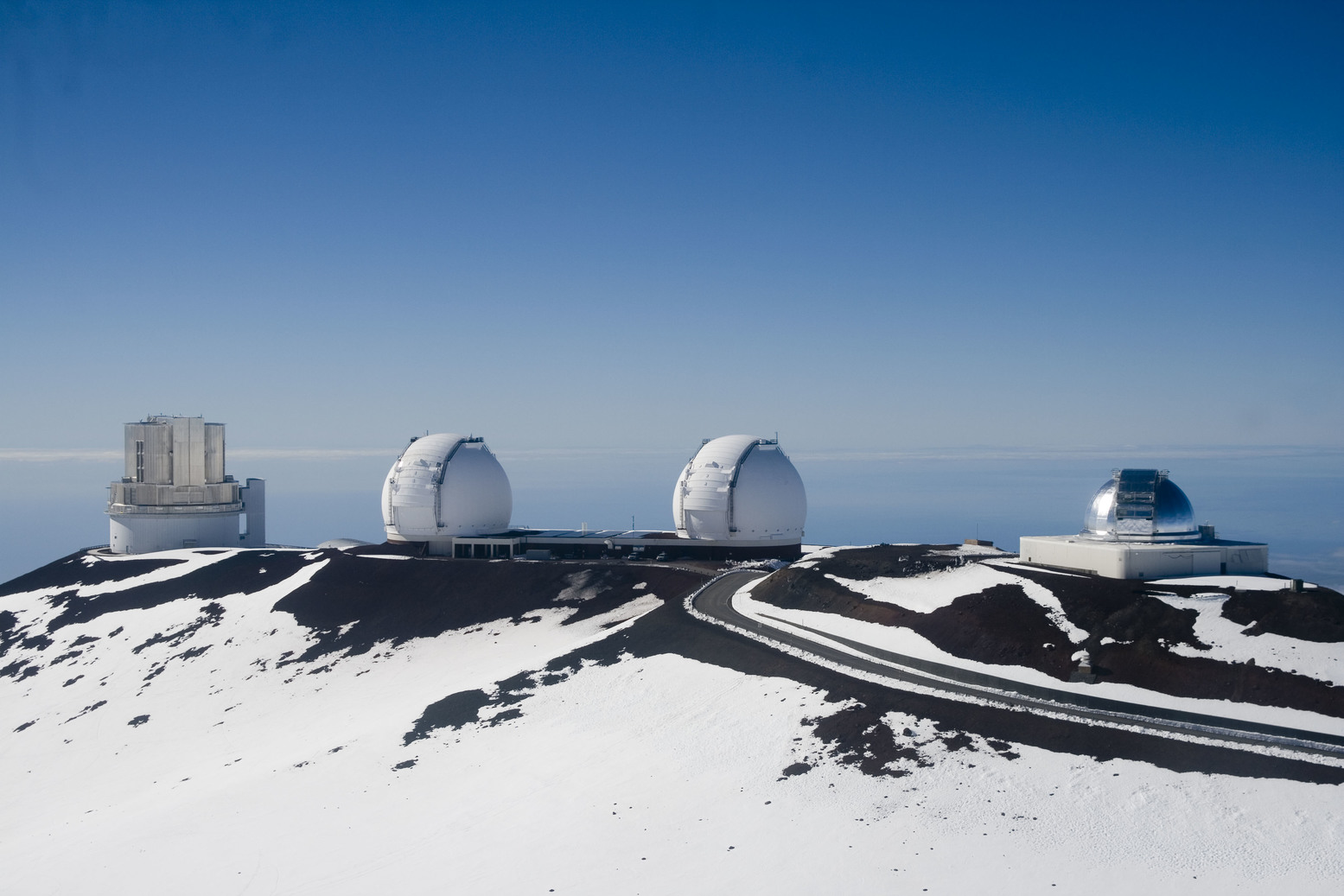

The summit itself where the observatories are is at 13,800' (4,205m) and it is recommend that visitors to the summit first acclimatise at the 9.200' point first for half an hour to an hour before proceeding.

At 13,800' the atmospheric pressure is 40 percent less than at sea level and Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is common. One survey revealed that some 69% of workers at the top of Mauna Kea

have experienced AMS at some point. AMS can be serious, including life-threatening conditions pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs) and cerebral edema (fluid on the brain).

Thankfully a well-graded gravel road allows for anyone who experiences AMS to be rapidly evacuated to below 10,000' where recovery is typically quick.

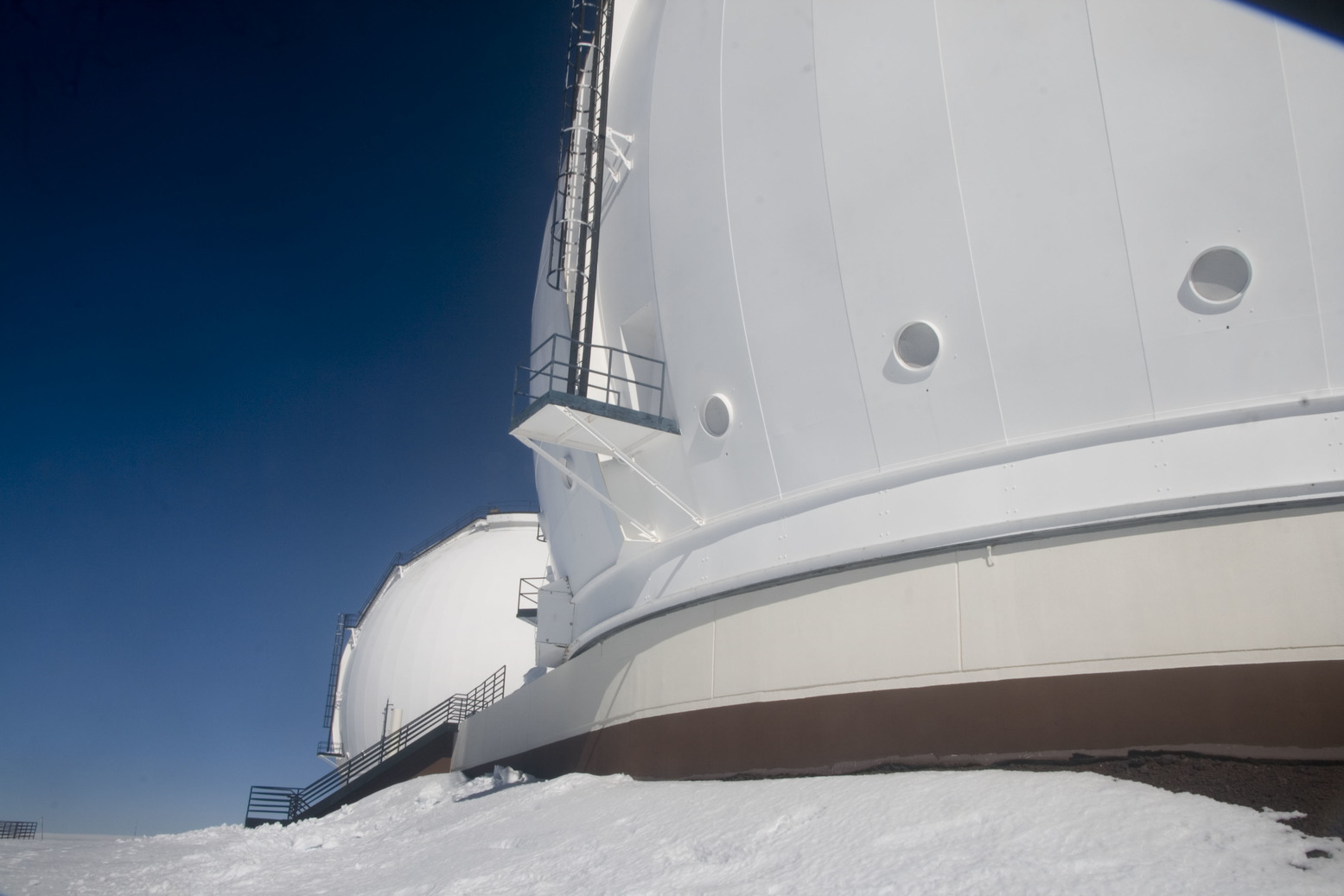

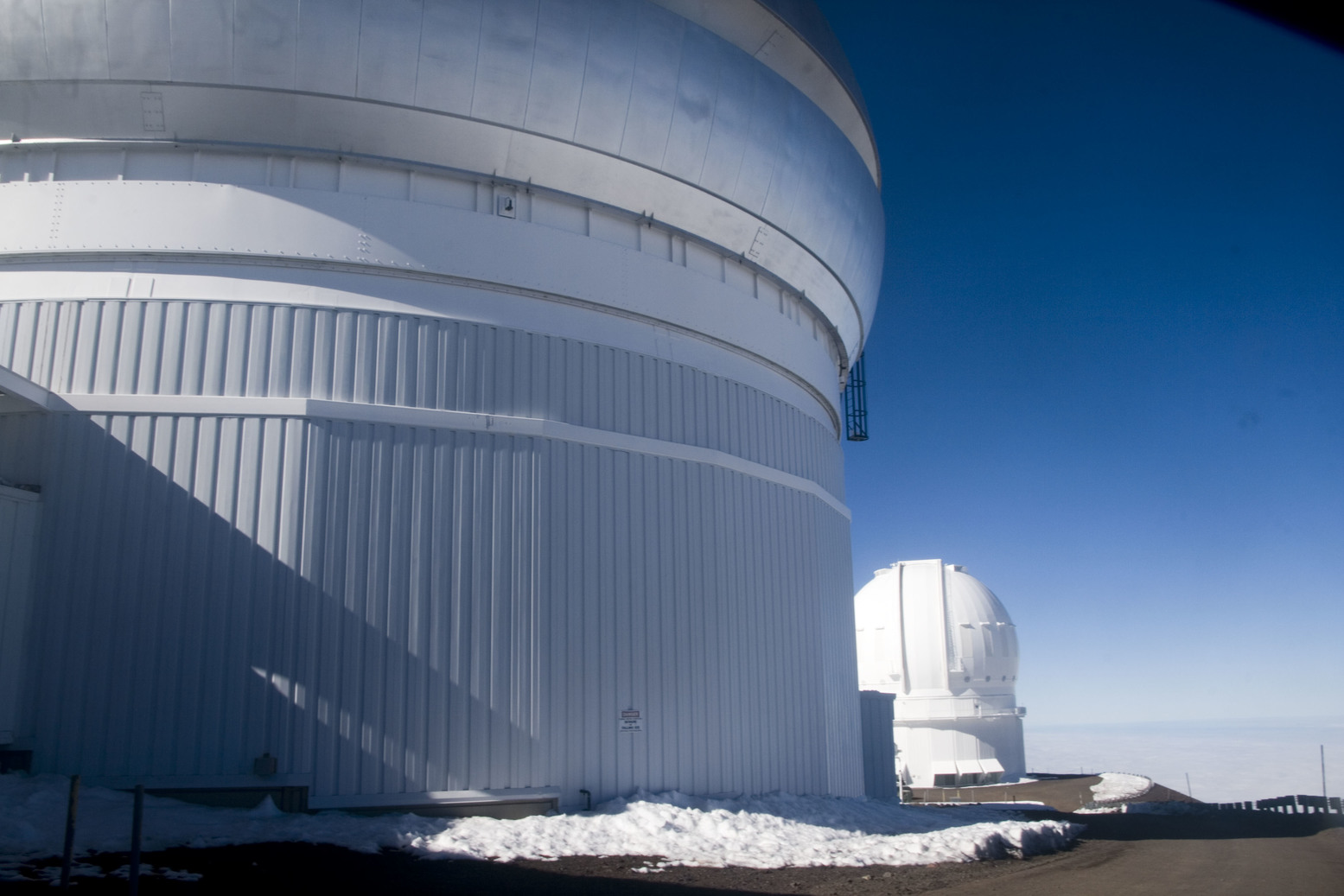

We were lucky to be given a VIP daytime tour of the Keck I observatory and our visit corresponded to a beautiful day at the peak.

The first thing that strikes you when you get out of the car is the definite diminished amount of air to breathe. You have to take things easy. It had been snowing up there and stooping over and throwing a couple of snowballs

would leave one feeling as if you had just run up several flights of stairs.

The observatory has O2 blood monitors and a check of our party gave us all the reassurance we were within normal levels. Emergency oxygen is available on site.

We were also afforded a VIP tour of the Keck mirror lab at the observatory headquarters in Waimea. There we were able to witness the multiyear painstaking refurbishment of the 72 mirror segments that constitute the two 10m mirrors on Keck I and Keck II.

Each mirror is equipped with multiple levers and actuators. One set positions each of the segments into its appropriate position to form a parabola. A second corrects for small imperfections within an individual segment. A third can distort the mirror by

microns thousands of times per second as part of the laser artifical star driven adaptive optics system.

One of the most remarkable attributes of our 9,200' observing point was the rapidity by which would get access it. During the day, we stayed at a beautiful rental house at 1000' altitude where the T-shirt and shorts temperature

both day and night was always perfect. It was only a 15 minute drive from there to the beach. Yet we could drive from the house to the 9,200' observing point via a high-speed highway and road in under 45 minutes.

In fact the road up is reputed to have one of the most rapid rises in the shortest amount of time for any road in the world.

Those wimps who climb Everest only have to climb 12,000 feet to get from Base Camp to the summit. On the Big Island you could ascend or descend through 13,800' in under a couple of hours including time

to acclimatise.

With our observing site at +12 North and with two of us having come from Sydney and five from the continental United States, the Aussies of course tended to want to seek out northern targets, particularly large

galaxies and the Americans southern targets. Thankfully there was plenty of time over our two week stay to do both.

Once Crux had risen, it was possible to see both it and Polaris at the same time.

Even familiar targets such as the Trio in Leo took on a new, fabulous appearance, Each galaxy so fantastically bright and extended.

On one occasion we observed until dawn which gave us the opportunity to witness a beautiful, dramatic and memorable sunrise ascend up through the clouds below us.

On another night we had the opportunity to observe with local astronomy club members at a 6000' location. Several of the club members worked at the Keck and it gave us a wonderful opportunity to chat to them about

work there and life on the Big Island.

We also took a road trip to the top of Mauna Loa which is home to the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO), which is the premier atmospheric research facility that has been continuously monitoring and collecting data related to atmospheric change since the 1950's.

This is the base station from which the Earth's ever-increasing CO2 levels are measured and depicted in the now famous Keeling Curve.

The one-lane, winding and undulating road to the summit of Mauna Loa goes through one of the most incredible landscapes on Earth, passing through vast solidified lava fields.

![[Logo]](/forum/templates/default/images/logo.jpg)